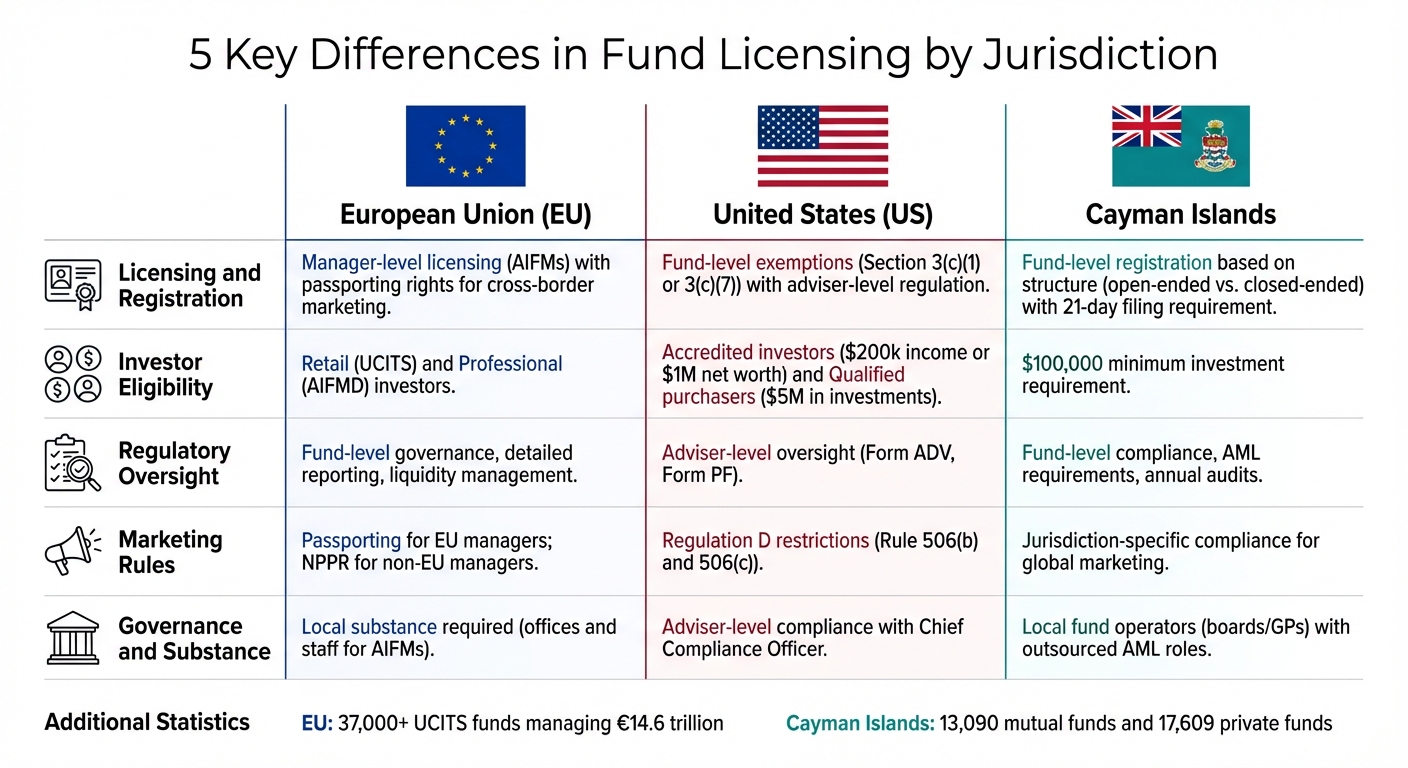

Fund licensing requirements vary significantly across regions, impacting how funds are structured, marketed, and managed. Here are the five main differences between the European Union (EU), United States (US), and Cayman Islands:

- Licensing and Registration:

- EU: Focuses on licensing fund managers (e.g., AIFMs) before funds operate, with passporting rights for cross-border marketing.

- US: Funds avoid direct registration by using exemptions (e.g., Section 3(c)(1) or 3(c)(7)), shifting regulation to fund advisers.

- Cayman Islands: Registration depends on the fund structure (open-ended vs. closed-ended), with strict timelines for compliance.

- Investor Eligibility:

- EU: Differentiates between retail (UCITS) and professional (AIFMD) investors.

- US: Uses wealth thresholds – accredited investors ($200k income or $1M net worth) and qualified purchasers ($5M in investments).

- Cayman Islands: Requires a $100,000 minimum investment, targeting institutional and high-net-worth investors.

- Regulatory Oversight:

- EU: Emphasizes fund-level governance, detailed reporting, and liquidity management.

- US: Prioritizes adviser-level oversight, requiring filings like Form ADV and Form PF.

- Cayman Islands: Focuses on fund-level compliance, including AML requirements and annual audits.

- Marketing Rules:

- EU: Passporting allows seamless cross-border marketing for EU-based managers; non-EU managers rely on National Private Placement Regimes (NPPR).

- US: Regulation D restricts general solicitation, with stricter rules under Rule 506(c).

- Cayman Islands: Marketing depends on target jurisdictions, with global compliance for onshore fundraising.

- Governance and Substance:

- EU: Requires local substance, including offices and staff for AIFMs.

- US: Focuses on adviser-level compliance, with a Chief Compliance Officer overseeing governance.

- Cayman Islands: Requires fund operators (e.g., boards or general partners) to register locally, with outsourced AML roles common.

Quick Comparison

| Feature | European Union (EU) | United States (US) | Cayman Islands |

|---|---|---|---|

| Licensing Focus | Manager-level (AIFMs) | Adviser-level (via exemptions) | Fund-level (open/closed structure) |

| Investor Eligibility | Retail (UCITS) & Professional (AIFMD) | Accredited ($200k income) & Qualified ($5M) | $100k minimum investment |

| Regulatory Oversight | Detailed fund-level governance | Adviser-focused reporting (Form ADV, PF) | Fund-level AML, audits, and filings |

| Marketing Rules | Passporting & NPPR | Regulation D (506(b) & 506(c)) | Onshore compliance for global marketing |

| Governance Requirements | Local presence & depositaries | Adviser compliance programs | Local fund operators & AML officers |

These differences shape how funds are structured, marketed, and managed across jurisdictions. Understanding these rules is essential for compliance and long-term success.

Fund Licensing Requirements Comparison: EU vs US vs Cayman Islands

Overview of Major Fund Licensing Jurisdictions

Fund licensing systems differ significantly across the EU, US, and Cayman Islands, each offering distinct approaches and benefits. The EU uses a product-focused system for retail funds and a manager-focused system for alternative funds. In the US, funds often rely on exemptions, avoiding registration by restricting investor types and numbers. Meanwhile, in the Cayman Islands, the focus is on the fund itself, requiring registration with the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (CIMA).

Each jurisdiction comes with its own perks. The EU’s framework allows for passporting, enabling cross-border distribution. The US provides access to the world’s largest capital market. The Cayman Islands offers tax neutrality and operates under a legal system rooted in English common law.

Looking at the numbers, the EU oversees more than 37,000 UCITS funds, managing assets of over €14.6 trillion. The US dominates the private fund sector through its accredited investor and qualified purchaser rules. The Cayman Islands, on the other hand, regulates nearly 13,000 open-ended funds and over 17,000 closed-ended funds. These differences highlight the unique licensing frameworks in each region.

European Union: AIFMD and UCITS Frameworks

The EU’s regulatory system is divided into two key components: the UCITS Directive and the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD). UCITS governs retail funds like mutual funds, while AIFMD focuses on non-retail funds such as hedge funds, private equity, and real estate funds. Both frameworks include passporting rights, with UCITS catering to retail investors and AIFMD targeting professional investors.

Recent updates have strengthened these frameworks. The UCITS VI Directive, effective March 18, 2024, introduced new liquidity management tools and standardized supervisory reporting. Similarly, a 2024 review of the AIFMD brought in specific rules for loan-originating AIFs and enhanced liquidity management requirements. Both now mandate fund managers to select at least two liquidity tools from a harmonized list to handle redemption pressures effectively. Oversight is shared between the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) and national authorities, with Luxembourg and Ireland serving as key domiciles for EU funds.

United States: Private Fund Exemptions

In the US, private funds avoid direct registration as investment companies by using exemptions under the Investment Company Act of 1940. Section 3(c)(1) limits a fund to 100 beneficial owners (or 250 for qualifying venture capital funds). Section 3(c)(7), however, allows unlimited owners, provided all are qualified purchasers – individuals with at least $5 million in investments.

For advisers, registration with the SEC is generally required if assets under management exceed $100 million. However, advisers managing only private funds with less than $150 million in AUM or those solely handling venture capital funds can qualify as Exempt Reporting Advisers (ERAs). ERAs avoid full SEC registration but must meet limited filing requirements. Additionally, the SEC’s Marketing Rule (Rule 206(4)-1) governs how private fund advisers present performance data and use third-party solicitations, following a principles-based approach.

Cayman Islands: Mutual Funds Act and Private Funds Act

The Cayman Islands takes a different approach by regulating funds based on their redemption structures. The Mutual Funds Act oversees open-ended funds, which allow investors to redeem their interests at will. In contrast, the Private Funds Act governs closed-ended funds, such as private equity and real estate funds, which do not permit voluntary redemptions. This contrasts with the EU and US, where regulation focuses more on the manager than the fund structure.

Since August 2020, regulatory oversight in the Cayman Islands has tightened. Previously unregulated "limited investor" funds – those with 15 or fewer investors – are now required to register with CIMA. Nearly all Cayman mutual funds are registered, with a minimum initial investment of $100,000. Private funds must file a registration application with CIMA within 21 days of accepting capital commitments from investors. For most mutual and private funds, initial and annual registration fees are approximately $4,481.71, while SIBA Registered Persons (managers) pay annual fees around $7,317.07.

Difference 1: When Licensing and Registration Are Required

The rules around when and how funds must be licensed or registered vary widely depending on the jurisdiction, creating different compliance pathways. In the European Union (EU), the focus is on licensing fund managers before any fund can operate. In the United States, private funds generally avoid registering the fund itself by using statutory exemptions, shifting the regulatory burden to fund advisers. Meanwhile, in the Cayman Islands, whether a fund must register depends on its structure – open-ended or closed-ended. Let’s take a closer look at how licensing and registration differ in these regions.

EU: Manager-Level Licensing Requirements

In the EU, the regulatory spotlight is on fund managers. Under the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD), managers of hedge funds, private equity funds, and real estate funds must secure authorization from their home country’s regulator before managing alternative investment funds. Similarly, UCITS funds require the fund itself to be authorized in a Member State, but this process hinges on having a licensed manager in place. Once a manager is authorized in one EU country, they can use passporting rights to market funds across other EU Member States without needing separate approvals. This “manager-first” approach means compliance obligations are tied to the entity managing the fund, shaping how funds in the EU are structured from the ground up.

US: Fund-Level Registration Exemptions

In the US, private funds avoid fund-level registration by relying on exemptions under the Investment Company Act. For instance, Section 3(c)(1) exempts funds with fewer than 100 beneficial owners, while Section 3(c)(7) allows funds with an unlimited number of investors, provided they are all qualified purchasers with at least $5 million in investments. Because of these exemptions, the regulatory focus shifts entirely to fund advisers, which heavily influences how private funds in the US approach their formation and compliance processes.

Cayman: Registration Based on Fund Structure

In the Cayman Islands, whether a fund must register depends on its structure. Open-ended funds are required to register before they can take in capital, while closed-ended funds must register with the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (CIMA) within 21 days of accepting investors. Failing to register can lead to fines of up to $120,000. This structure-focused approach creates distinct compliance timelines, which play a key role in shaping fund formation strategies in the region.

Difference 2: Investor Eligibility and Offering Rules

Investor eligibility rules vary significantly depending on where a fund is domiciled. In the EU, the system distinguishes between retail and professional investors, while the US relies on wealth thresholds to define eligibility. The Cayman Islands, meanwhile, uses minimum investment amounts as a gatekeeper. These variations influence how funds are structured, marketed, and distributed. Let’s take a closer look at how investor requirements in each jurisdiction shape fund design.

EU: Professional vs. Retail Investor Requirements

The EU operates on a dual-track system that caters to two distinct investor groups. UCITS funds are designed for retail investors – the general public – and enjoy the ability to be marketed freely across all EU Member States through passporting rights. This framework has become the global benchmark for retail fund distribution, with UCITS funds marketed in 77 countries worldwide. However, these funds must adhere to stringent rules regarding liquidity, transparency, and investor protection.

On the other hand, AIFMD funds are tailored for professional investors – those with the expertise and resources to evaluate risks independently, as defined under MiFID II criteria. These funds include vehicles like hedge funds, private equity, and real estate investments. AIFMD funds can also benefit from passporting rights, but only for professional investors. Retail marketing is generally prohibited unless specific national regulations allow it. This distinction forces fund managers to decide early whether they aim to serve the mass retail market or focus on institutional and professional capital.

US: Accredited and Qualified Purchaser Standards

In the US, investor eligibility is determined by wealth thresholds. Accredited investors are individuals with an annual income of at least $200,000 (or $300,000 jointly with a spouse) or a net worth exceeding $1 million, excluding their primary residence. These investors are eligible to participate in most private offerings under Regulation D. For those seeking to access funds under the Section 3(c)(7) exemption, the bar is set even higher – qualified purchasers must have at least $5 million in investments.

These wealth-based criteria are built on the assumption that financially sophisticated investors are better equipped to handle the risks associated with unregistered investment vehicles. The thresholds directly impact fund structure: managers targeting a larger pool of accredited investors often use Section 3(c)(1), while those focused on institutional capital and unlimited scale prefer Section 3(c)(7). Unlike the EU, where retail investors have access to UCITS funds, private funds in the US are reserved for high-net-worth and institutional investors.

Cayman: Minimum Investment Requirements

The Cayman Islands takes a different approach, using minimum investment amounts to define its investor base and regulatory framework. Cayman funds typically require a minimum subscription of $100,000, which qualifies them for lighter regulatory oversight under the Mutual Funds Act. This threshold serves as a proxy for investor sophistication – funds that accept smaller investments from less experienced investors are subject to stricter licensing and oversight by CIMA.

This setup appeals to global institutional investors, family offices, and high-net-worth individuals who are drawn to the tax-neutral benefits of Cayman funds. By setting a high minimum investment, Cayman funds attract a specific type of investor from the outset, making them particularly attractive to managers focused on institutional and ultra-high-net-worth capital rather than retail participation.

Difference 3: Regulatory Oversight and Compliance Requirements

Once a fund is established, staying compliant becomes an ongoing responsibility. However, the compliance landscape varies widely depending on the jurisdiction. The EU has detailed governance and reporting rules, the US focuses more on investment advisers, and the Cayman Islands offers a lighter regulatory touch combined with robust anti-money laundering (AML) measures and local audit requirements.

EU: Governance and Reporting Under AIFMD

The EU’s Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD) sets strict oversight standards for both funds and their managers. Fund managers must regularly report detailed data – covering markets, exposures, and risk management – to their respective National Competent Authorities (NCAs). In addition, AIFMD requires alternative investment funds to appoint a depositary to safeguard assets and oversee cash flows.

The 2024 review of AIFMD introduced new layers of compliance. Managers are now obligated to select at least two liquidity management tools from an approved list to handle redemption pressures effectively. Loan-originating funds also face specific regulatory rules, reflecting the EU’s attention to non-bank lending practices. Since reporting is done at the national level, fund managers must directly engage with NCAs to meet filing requirements, including specific XML schema formats.

While the EU focuses heavily on fund-level governance, the US takes a different approach, prioritizing adviser-level oversight.

US: Adviser-Level Reporting Requirements

In the US, regulatory oversight primarily targets investment advisers rather than the funds themselves. Registered Investment Advisers are required to file Form ADV, which details their business practices, fee structures, conflicts of interest, and any disciplinary history. They must also file Form PF to provide the SEC with data on systemic risk, leverage, and liquidity.

This adviser-centric model means that private funds, when operating under certain exemptions, face minimal direct regulatory scrutiny. However, the advisers managing these funds must adhere to strict disclosure and fiduciary duties. Unlike the EU’s dual focus on funds and managers, the US keeps the spotlight on the advisers.

In contrast, the Cayman Islands takes a more comprehensive approach at the fund level.

Cayman: CIMA Compliance Requirements

In the Cayman Islands, regulatory compliance revolves around fund-level obligations. All funds registered with the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (CIMA) – whether mutual or private – must file annual audited financial statements through a CIMA-approved auditor, with reports due within six months after the end of the financial year. Registration fees are structured based on a predefined schedule.

The Cayman framework emphasizes AML and know-your-customer (KYC) protocols. Every fund must appoint an AML Compliance Officer (AMLCO), a Money Laundering Reporting Officer (MLRO), and a Deputy MLRO. Additionally, directors of mutual funds and managers of LLCs must register or obtain licenses under the Directors Registration and Licensing Act.

Closed-ended funds, regulated under the Private Funds Act, face additional operational requirements. These include annual asset valuations, independent monitoring of cash flows, and arrangements for asset safekeeping or custody. The 2023 Beneficial Ownership Transparency Act has further tightened compliance. Funds must maintain a beneficial ownership register or appoint a licensed administrator as a “contact person” to provide information to authorities within 24 hours of a request. CIMA has also shifted toward active enforcement, with fines ranging from $5,000 for minor violations to $1 million for severe breaches.

"The Cayman Islands’ recent beneficial ownership reforms strike a careful balance between transparency and privacy, ensuring compliance with global AML standards while protecting legitimate business confidentiality." – Tom Katsaros and Wei Xun Toh, Carey Olsen Singapore LLP

For fund managers in the Cayman Islands, outsourcing compliance tasks can be a practical solution. Services like those offered by Charter Group Fund Administration help managers navigate local requirements efficiently. From AML to CRS and FATCA compliance, these outsourced services allow managers to meet CIMA’s stringent standards without needing to build internal compliance teams. This approach reflects how Cayman’s regulatory framework balances thorough compliance with operational flexibility.

sbb-itb-9792f40

Difference 4: Marketing and Cross-Border Distribution Rules

When it comes to marketing funds across borders, the rules vary significantly depending on the jurisdiction. In the EU, a streamlined passport system simplifies the process for authorized managers. The US, however, enforces strict restrictions on general solicitation, while the Cayman Islands require managers to navigate specific onshore regulations in each target market. These varying frameworks play a key role in shaping how funds raise capital internationally.

EU: AIFMD Passport and National Private Placement

The EU’s AIFMD passport system provides a straightforward way for authorized managers based in the EU to market funds across all 27 member states. This process involves a simple notification to the manager’s home regulator – such as Luxembourg’s CSSF – who then informs the host regulator. Marketing can typically begin within 20 working days, creating a cohesive distribution network across the European Economic Area, as long as both the manager and the fund are EU-domiciled.

For non-EU managers, the process isn’t as seamless. They must rely on National Private Placement Regimes (NPPR), which differ from one country to another in terms of fees, rules, and requirements. For example:

- Austria charges a processing fee of €1,100 plus €220 per sub-fund.

- Croatia imposes a fee of around €8,600.

- Denmark requires non-EU managers to appoint a "depo-light" service provider and submit a reciprocity statement from their home regulator.

"The diversity of the domestic rules makes it challenging for AIFMD authorised managers to assess the costs and various other requirements for penetrating the EU market." – CMS Guide to Passporting

The EU also has strict rules on pre-marketing activities. While managers can gauge investor interest before formally registering a fund, de-notifying a fund in any specific country triggers a 36-month ban on pre-marketing similar investment strategies in that jurisdiction.

US: Regulation D and Marketing Restrictions

In the US, Regulation D governs private fund marketing with two key rules. Rule 506(b) prohibits general solicitation, meaning managers must rely on pre-existing relationships with investors. On the other hand, Rule 506(c) permits public marketing but only if every investor meets strict accreditation criteria, verified through income or net worth thresholds. While this rule provides flexibility, it also increases administrative burdens and limits marketing options.

Additionally, US private funds face hurdles when marketing internationally, as they must adhere to the securities laws of each target jurisdiction, adding complexity to global fundraising efforts.

Cayman: Marketing to Global Investors

Cayman Islands funds operate under a different set of marketing rules. For non-Cayman managers of Cayman-domiciled funds, there’s no requirement to be regulated locally, which helps keep operating costs low.

However, when targeting EU investors, Cayman funds must register under National Private Placement Regimes, as the AIFMD passport is restricted to EU-domiciled funds with EU-based managers. Some managers attempt to use reverse solicitation, where investors initiate contact, but regulators closely monitor this practice to ensure compliance.

When marketing to US investors, Cayman funds must adhere to Regulation D. Meanwhile, those reaching out to European investors are increasingly expected to align with ESG disclosure standards under SFDR, even though Cayman law does not mandate such disclosures. For effective global distribution, many Cayman funds depend on placement agents familiar with local marketing laws. Managers must carefully oversee these agents and set clear guidelines for each market.

To support global marketing efforts, Charter Group Fund Administration assists Cayman fund managers with compliance tasks like AML, CRS, and FATCA reporting. This allows managers to focus on building relationships with investors while ensuring they meet regulatory requirements across multiple jurisdictions. These marketing regulations, in combination with licensing and compliance rules, significantly influence fund structuring decisions worldwide.

Difference 5: Substance and Governance Requirements

Governance rules for funds vary significantly depending on the jurisdiction. The European Union (EU) emphasizes local substance, the United States (US) focuses on adviser-level oversight, and the Cayman Islands prioritizes fund operators with moderate onshore support. These differences in governance, along with earlier variations in licensing and marketing, play a critical role in shaping a fund’s structure and operational approach.

EU: Local Presence and Substance Requirements

The EU’s Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (AIFMD) centers governance on the Alternative Investment Fund Manager (AIFM), rather than the fund itself. AIFMs need to establish a real presence within the EU, complete with local offices and staff, to avoid being labeled as shell or "letterbox" entities.

In key EU jurisdictions like Luxembourg, managers must handle portfolio and risk decisions locally while appointing an independent depositary to safeguard assets. They also face strict reporting requirements on leverage, liquidity, and risk to National Competent Authorities. The 2024 AIFMD revisions added harmonized rules for liquidity management tools, further increasing compliance complexity.

US: Adviser-Level Governance Standards

Unlike the EU, US regulations focus on the adviser rather than the fund. The Investment Advisers Act requires registered advisers to implement robust compliance programs overseen by a Chief Compliance Officer (CCO). The CCO is tasked with developing written policies, conducting annual reviews, and ensuring adherence to SEC regulations. While the funds themselves face fewer direct governance mandates, advisers must address key areas like conflicts of interest, valuation procedures, and custody arrangements across all managed vehicles.

Cayman: Director and Substance Standards

In the Cayman Islands, governance revolves around the fund operator – either the Board of Directors for exempted companies or the General Partner (GP) for Exempted Limited Partnerships (ELPs). As of Q2 2025, the Cayman Islands hosted 13,090 mutual funds and 17,609 private funds. Directors of funds regulated by the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (CIMA) must register under the Director Registration and Licensing Act, and fund operators must include at least two natural persons to ensure active oversight.

CIMA’s Governance Rule requires regulated funds to hold at least one annual meeting, where directors review the fund’s activities, strategy, and compliance framework. While investment managers can be based offshore, Cayman funds must maintain a local auditor and registered office. For ELPs, at least one GP must qualify as a Cayman resident or a registered foreign entity.

Additionally, Cayman funds must appoint three Anti-Money Laundering (AML) roles – an AML Compliance Officer (AMLCO), a Money Laundering Reporting Officer (MLRO), and a Deputy MLRO. These roles are often outsourced to professional service providers. Notably, investment funds are exempt from the Economic Substance Act.

"The 2020 Private Funds Act represented a watershed moment. By introducing mandatory registration, annual audit requirements, and formalised oversight mechanisms for valuation and custody, Cayman elevated its regulatory posture without sacrificing commercial viability."

- Samantha Widmer, Associate Director of Funds and Capital Markets, Cayman Finance

For fund managers operating in the Cayman Islands, firms like Charter Group Fund Administration provide essential compliance support, including AML officer services and beneficial ownership register maintenance. This allows fund operators to meet CIMA’s governance requirements while concentrating on their core strategies.

| Feature | European Union | United States | Cayman Islands |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Governance Level | Management Company (AIFM) | Investment Adviser | Fund Operator (Board/GP) |

| Local Presence | High (Physical office/staff) | Adviser-level presence | Moderate (Local auditor/office) |

| Director Requirements | Manager-level fitness review | Fiduciary duty of Adviser | CIMA Director Registration |

| Key Compliance Role | Conducting Officers | Chief Compliance Officer | AMLCO, MLRO, DMLRO |

| Annual Meeting | Regulatory reporting cycles | Adviser compliance reviews | Mandatory fund-level meeting |

Conclusion: How These Differences Affect Fund Structuring

Key factors like licensing requirements, investor eligibility, regulatory oversight, marketing rules, and governance standards heavily influence fund structuring. These elements shape decisions ranging from how funds are organized to how investors are verified. For instance, managers aiming to attract U.S. tax-exempt institutions and non-U.S. investors often opt for Cayman Islands Exempted Limited Partnerships (ELPs) when setting up closed-ended funds. This choice is driven by the tax neutrality and flexible structuring options these partnerships offer. Meanwhile, Cayman Unit Trusts are particularly appealing in Asian markets like China and Japan, where they align with local tax practices and provide regulatory benefits.

Timing for registration is another critical consideration. Cayman private funds must register within 21 days of admitting investors and before receiving capital. To qualify for the streamlined Registered Mutual Fund category and avoid more stringent requirements, sponsors should set a minimum initial investment of $100,000. Once all documentation is submitted, the registration process typically takes about five business days.

Since most Cayman funds operate without in-house staff, managers are required to designate third-party service providers to fulfill key roles, such as Anti-Money Laundering Compliance Officer (AMLCO), Money Laundering Reporting Officer (MLRO), and Deputy MLRO. U.S.-based sponsors marketing under Rule 506(c) must also implement thorough procedures to verify the accredited status of investors.

Specialized administrators play a crucial role in easing operational complexities. For example, Charter Group Fund Administration provides essential back-office services like NAV calculations, fund accounting, investor due diligence, and compliance with global standards, including AML, FATCA, and CRS. For Cayman funds, administrators also handle key responsibilities such as providing the principal office and conducting independent NAV calculations, as mandated by CIMA’s operational rules. This allows fund managers to concentrate on their investment strategies while ensuring compliance across multiple jurisdictions.

"The efficient and commercial success of such multi‑jurisdictional transactions invariably rests on the competence and experience of the legal counsel teams engaged to negotiate and advise the parties in respect of each relevant jurisdiction."

- Catharina von Finckenhagen, Partner, Travers Thorp Alberga

FAQs

What are the key differences between the AIFMD and UCITS frameworks for fund managers in the EU?

The AIFMD (Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive) lays out a comprehensive set of rules for managing alternative investment funds within the EU. These regulations include requirements for licensing, maintaining sufficient capital, managing risks, and adhering to reporting and transparency standards. The goal is to ensure that alternative investment funds operate under strict oversight.

On the other hand, the UCITS (Undertakings for the Collective Investment in Transferable Securities) Directive is centered around protecting retail investors. It provides a standardized framework that allows authorized fund managers to establish and market funds across the EU. These funds must comply with stringent rules designed specifically to safeguard the interests of individual investors.

While both directives aim to strengthen market stability and boost investor trust, they cater to distinct types of funds and investor groups.

What are the main compliance requirements for Cayman Islands funds?

Funds operating in the Cayman Islands must adhere to specific regulations based on their structure. Open-ended funds are regulated by the Mutual Funds Act, while closed-ended funds fall under the Private Funds Act. Regardless of type, both must register with the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (CIMA) and engage a fund administrator licensed by CIMA.

Fund directors are required to register under the Director Registration and Licensing Law, and the investment manager must be authorized under the Securities Investment Business Act. Additionally, funds must maintain audited financial statements, create a comprehensive offering memorandum, and comply with ongoing regulatory requirements, including AML and CRS standards. All documentation and fees are submitted through CIMA’s REEFS portal.

What are the key differences in investor eligibility rules between the U.S. and the EU?

Investor eligibility rules in the United States and the European Union differ greatly because of their distinct regulatory systems.

In the U.S., private fund offerings are typically limited to accredited investors or qualified purchasers. To qualify as an accredited investor, individuals must meet specific financial criteria, such as earning an annual income of at least $200,000 (or $300,000 combined with a spouse) or holding a net worth of $1 million, excluding the value of their primary residence. Qualified purchasers, on the other hand, are defined under U.S. securities laws as those with at least $5 million in investment assets. These requirements aim to ensure that only financially experienced and well-resourced individuals or entities can access private investment opportunities.

In the EU, investor classification follows a different approach, dividing individuals into retail and professional categories under regulations like MiFID II and AIFMD. Retail investors are afforded greater protections and more detailed disclosures, while professional investors – deemed to have the knowledge and resources to assess risks – are subject to fewer regulatory safeguards. Funds targeting professional investors often utilize private placement or reverse solicitation methods, which come with less stringent compliance requirements compared to offerings aimed at retail investors.

Essentially, the U.S. relies on wealth and income thresholds to determine investor eligibility, while the EU uses a classification system that separates retail and professional investors, tailoring regulatory oversight to each group.